On 27 January, we are going to commemorate the 75th anniversary of the liberation of the Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp. Given this context, the performance of Udo Zimmermann’s Weisse Rose presented during this year’s Opera Rara Festival became even more powerful.

On 27 January, we are going to commemorate the 75th anniversary of the liberation of the Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp. Given this context, the performance of Udo Zimmermann’s Weisse Rose presented during this year’s Opera Rara Festival became even more powerful. The history of the German anti-Nazi student organisation, which manifested their opposition against the authorities and called upon society to unite against the rulers has not been forgotten – and definitely not by the world of opera. Udo Zimmermann returned to the subject a couple of times. As a university student, he scored his brother’s libretto, and more than a decade later, he started working with the text by Wolfgang Willaschk. Weisse Rose is devoid of dramatic plot – instead, the piece focuses on the analysis of the protagonists’ emotional states in the final moments of their lives. Seeing their impending demise, the Scholl siblings – Sophie and Hans – gradually lose the clarity of their thoughts, delve deep into their memories and give in to unreal, idyllic fantasies (Sophie) and nightmarish visions (Hans). By standing in opposition to the authorities they did not believe in and calling upon the society to view them from a critical point of view, they raised the universal subject of awakening the nation and speaking against evil and injustice.

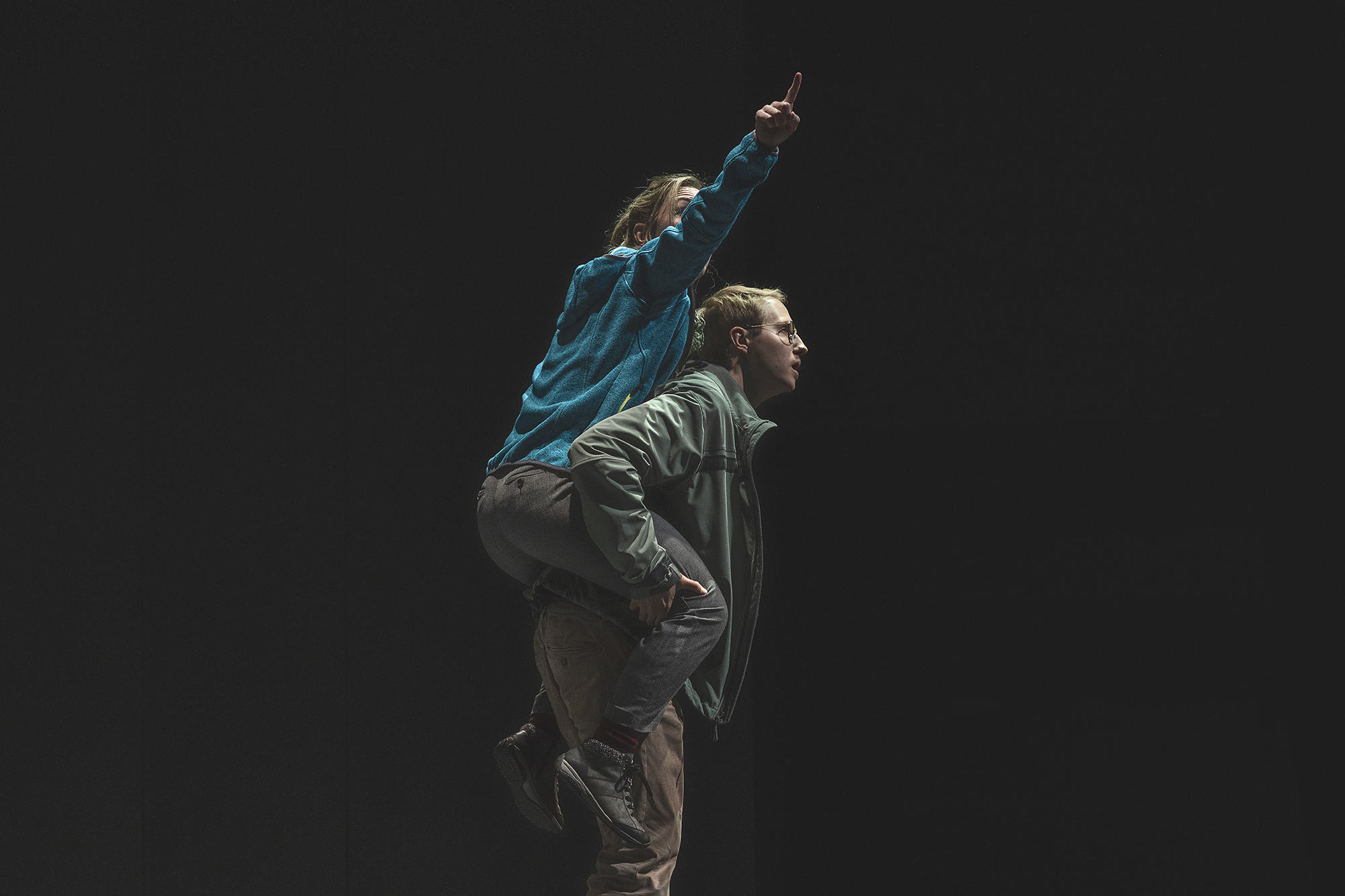

Focusing on the protagonists’ emotions and experiences, the analysis of a gradual descent into madness and the very way the music was created clearly allude to the Expressionists of the first half of the 20th century – its Viennese representatives chief among them. The musicians of Sinfonie Orchester Biel Solothurn built the tension by playing anxiety-inducing ostinatos – personally, I could not get the repeating harp leitmotif out of my head for quite a while – coupled with sudden dynamic and texture contrasts. The instruments employed opened up a vast space for sound experiments. The delicate, oneiric sounds (especially the harp, violins and flute) were juxtaposed with brutal and blunt ones, while both in music and the libretto, reality mixed with fantasy, underscored by colourful and flickering sound spots. I found the a cappella parts the most poignant – due to the accompanying sense of loneliness and fear. The voices of Marion Grange (soprano) and Wolfgang Resch (baritone) meshed perfectly with each other, and their singing was clearly unforced, free and honest. Their performances were devoid of wild vibratos and exuberant interpretations – instead, their singing was full of simplicity and authenticity, despite having to perform difficult parts based on far-reaching changes in melody.

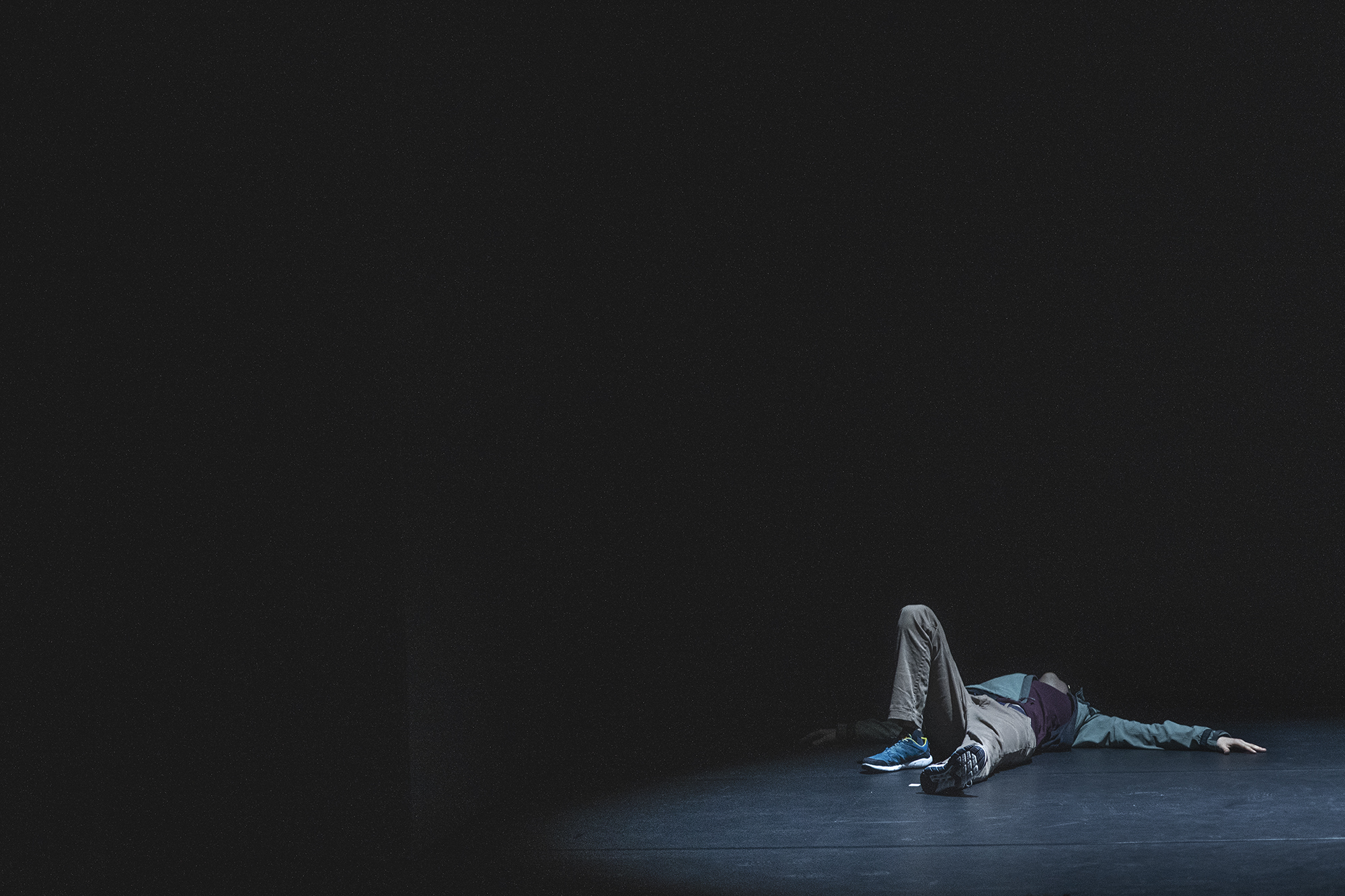

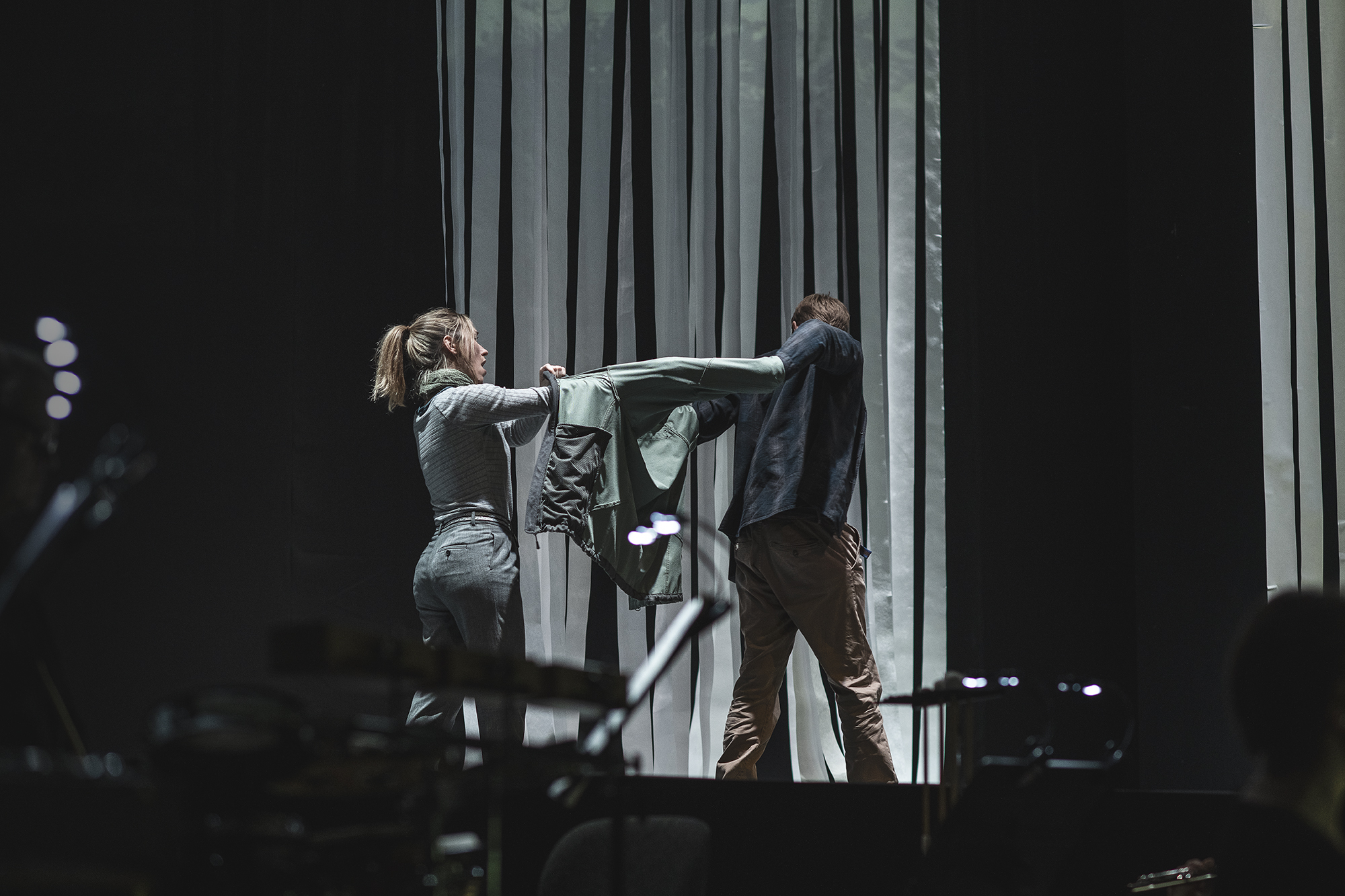

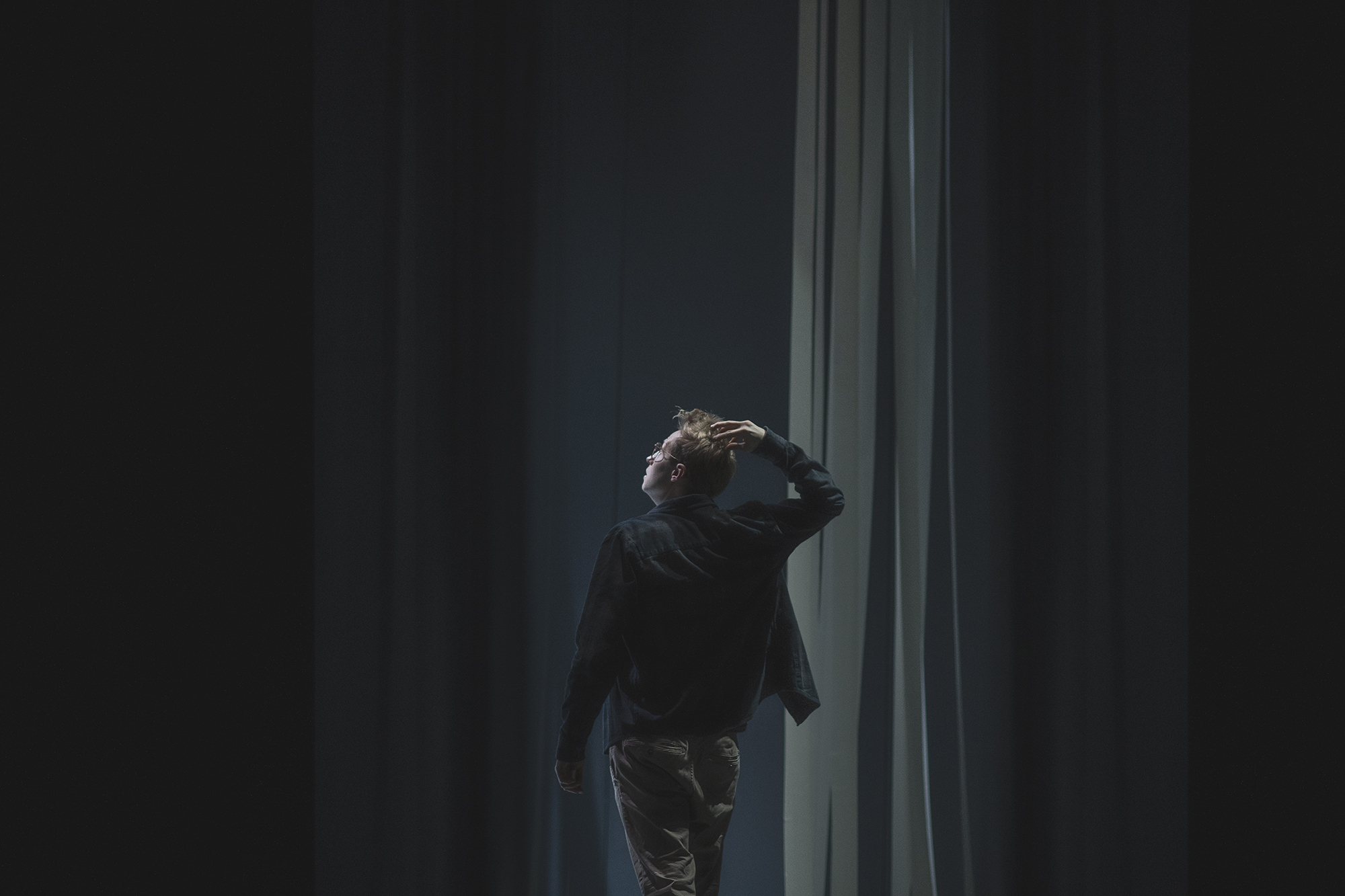

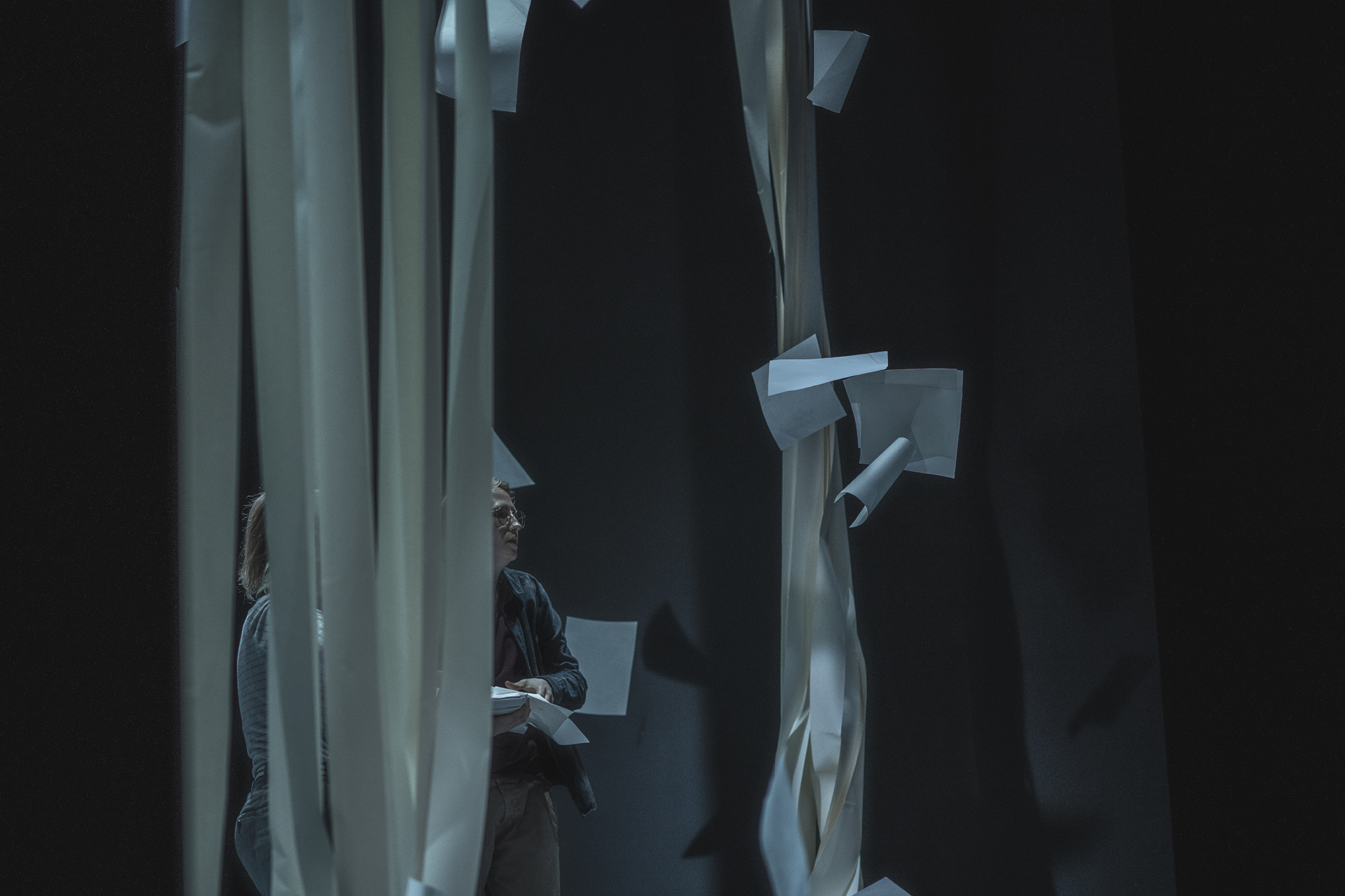

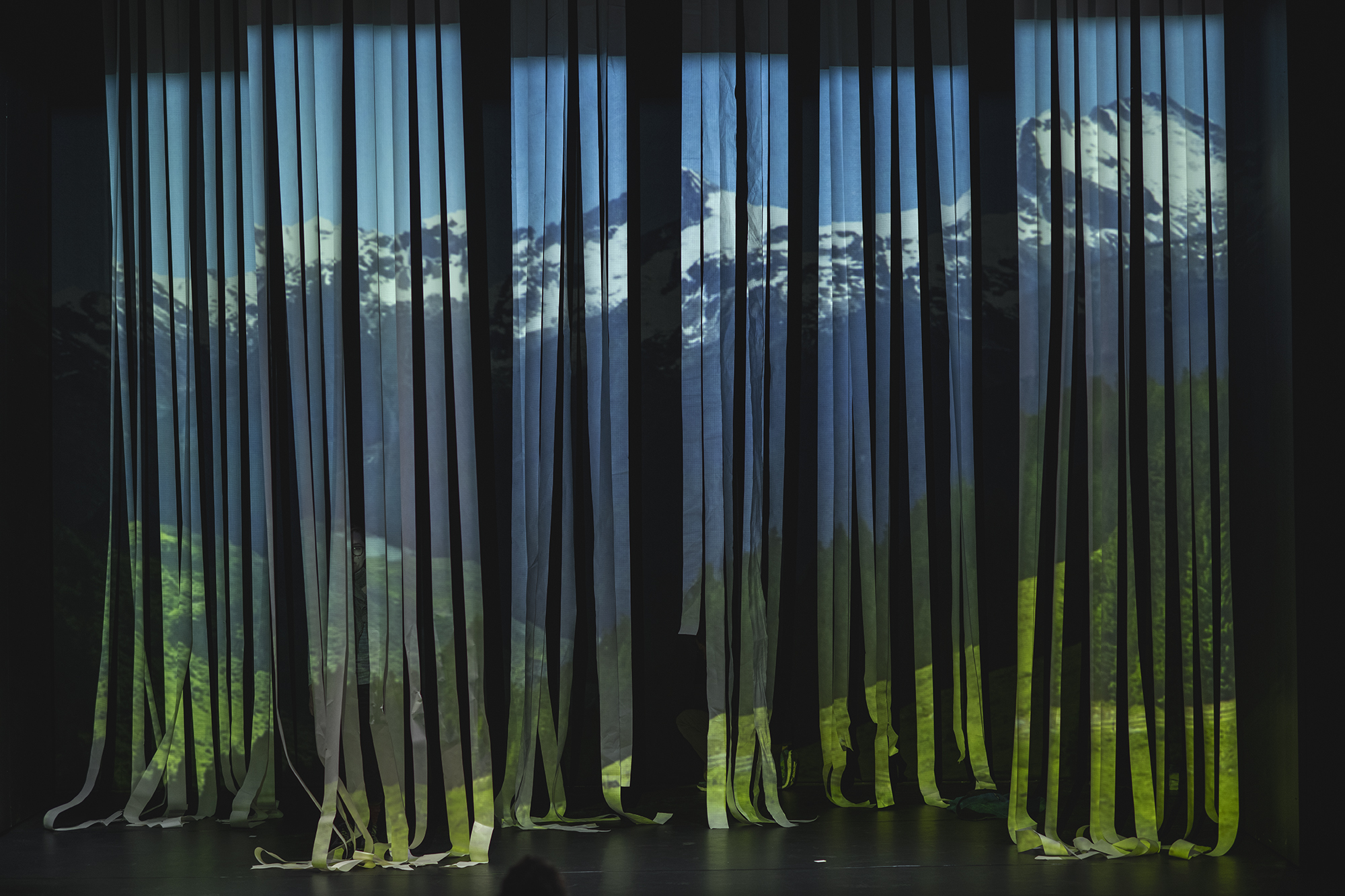

The raw and dark hall of the Małopolska Garden of Arts made for a perfect set for the award-winning staging by Anna Drescher. The changes in her minimalist stage design emerged along with the growing anxiety of the protagonists, whose world – even the imaginary one – kept gradually falling apart. Do Sophie and Hans actually live in the same reality? They both crave closeness, warmth and touch of another human being, while not seeing each other – the entire work has only a few parts where they sing together.

Willaschk’s libretto does not distort the facts – the siblings are going to die, yet they are willing to uphold their beliefs to the bitter end. The final scene is a manifesto – a call to the audience, urging them to oppose indifference towards harm, stupidity and hostility. Despite its pastoral sound, the excerpt from Franz Schubert’s Piano Quintet in A major, which clearly refers to his Die Forelle, which rang out at the end of the opera, gained a new stronger meaning in the context of Zimmermann’s piece – even in seemingly calm times, we need to be vigilant to see the danger threatening our freedom in time.

Maryla Zając for the Krakow Festival Office

- fot. Edyta Dufaj

- fot. Edyta Dufaj

- fot. Edyta Dufaj

- fot. Edyta Dufaj

- fot. Edyta Dufaj

- fot. Edyta Dufaj

- fot. Edyta Dufaj

- fot. Edyta Dufaj

- fot. Edyta Dufaj

- fot. Edyta Dufaj

- fot. Edyta Dufaj

- fot. Edyta Dufaj

- fot. Edyta Dufaj

- fot. Edyta Dufaj

- fot. Edyta Dufaj

- fot. Edyta Dufaj

- fot. Edyta Dufaj

- fot. Edyta Dufaj