5 days, 139 participants and 64 meetings, workshops and presentations – these are the numbers for the event that inaugurated the CELA project, in which we took between 13 and 17 of January in Brussels. Before us are 4 years of international collaboration on developing the book market in Europe and professionalising the activities of writers and translators in foreign markets.

CELA, or Connecting Emerging Literary Artists, is a programme that offers three emerging authors and translators the opportunity to meet artists from other European countries, take part in educational courses, consult their work with mentors and present it to publishers and literary agents at festivals in Poland and abroad. Krakow UNESCO City of Literature represents the Polish team, who were all in attendance at last week’s meeting of authors and the literary industry from ten European countries. Alongside us, representatives of Belgium, Italy, Spain, Serbia, Portugal, Czechia, Slovenia, Romania and the Netherlands are participating in the project. The week in Brussels was the first opportunity for the participants to get to know each other, exchange good practices in the field of functioning of literary institutions in their countries of origin, and jointly defined an action plan for the next four years. We’re going to roll up our sleeves because our common goals require organised, systematic work by all project partners. As the Dutch organisation Wintertuin – the project organisers – argue, talented writers and translators can only build an international careers based on translated literary works, and the results of their work will not be visible abroad without the right competences and an efficient network within the industry. The defined gaps in the European literary market, which CELA aims to reduce include differences between national and international book markets – especially for the so-called smaller languages – and the gap between the traditional book industry and the system of circulation of literary works in the digital age.

There will be many more opportunities to meet. Specialist courses for writers selected for the project, masterclasses for translators and internships for literary life animators representing partner institutions will be held until March next year. The whole cycle will end with an almost two-week course in creative non-fiction writing in Krakow, UNESCO City of Literature. Three months later, the texts written by the participating writers will be published, translated in each case into the other languages of the project participants. CELA will then change its image – the task for both us and our other partners will be to promote the resulting works. You can expect meetings with the authors at, for example, the 13th edition of the Conrad Festival in 2021.

Last year, the Krakow Festival Office conducted a call for proposals, in which the artists who make up the Polish representation in this edition of the CELA programme were selected. Translators of the selected languages into Polish are Aleksandra Wojtaszek (Serbian), Agata Wróbel (Czech), Gabriel Borowski (Portuguese), Mateusz Kłodecki (Italian), Olga Bartosiewicz-Nikolaev (Romanian), Olga Niziołek (Dutch), Ewa Dynarowicz (Dutch), Katarzyna Górska (Spanish) and Joanna Borowy (Slovenian). The selected translators will translate texts from the native languages of the organisations involved in the project. Three Polish writers will take part in the project: Joanna Gierak-Onoszko (author of 27 śmierci Toby’ego Obeda, Dowody na Istnienie), Aleksandra Lipczak (Ludzie z Placu Słońca, Dowody na Istnienie) i Urszula Jabłońska (Człowiek w przystępnej cenie. Reportaże z Tajlandii, Dowody na Istnienie).

We are thrilled to be part of the team creating the international CELA brand together! We will keep you informed about further activities that are changing the shape of the publishing market in Europe and building bridges between different sectors of the literary industry – regardless of the borders dividing us.

You will be able to follow the results of the CELA project at cela-europe.com, Facebook and Instagram.

International travels of programme participants, as well as literary courses and residencies are carried out with financial support of the European Union under the Creative Europe Programme.

Photo: Gaby Jongenelen

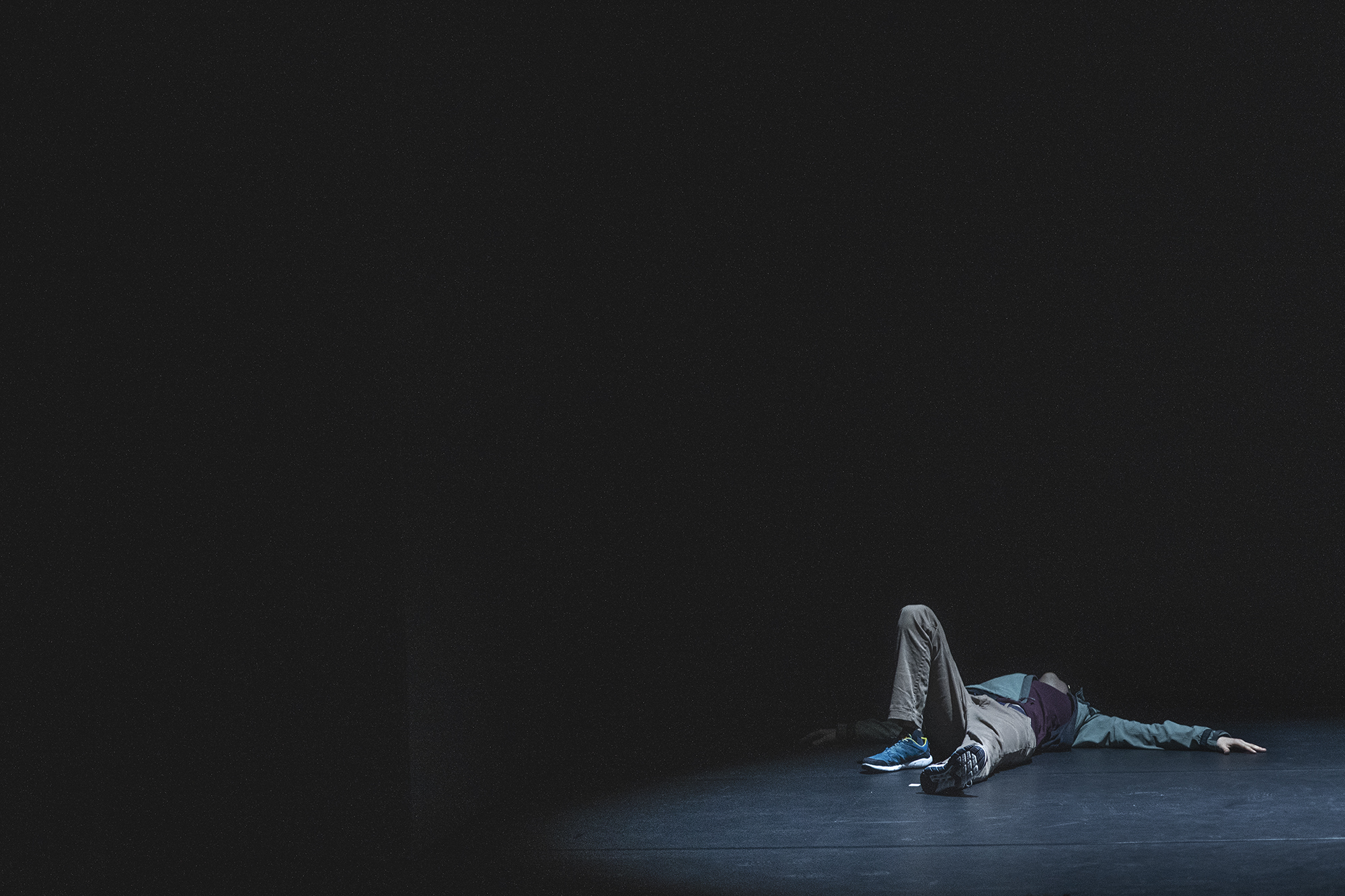

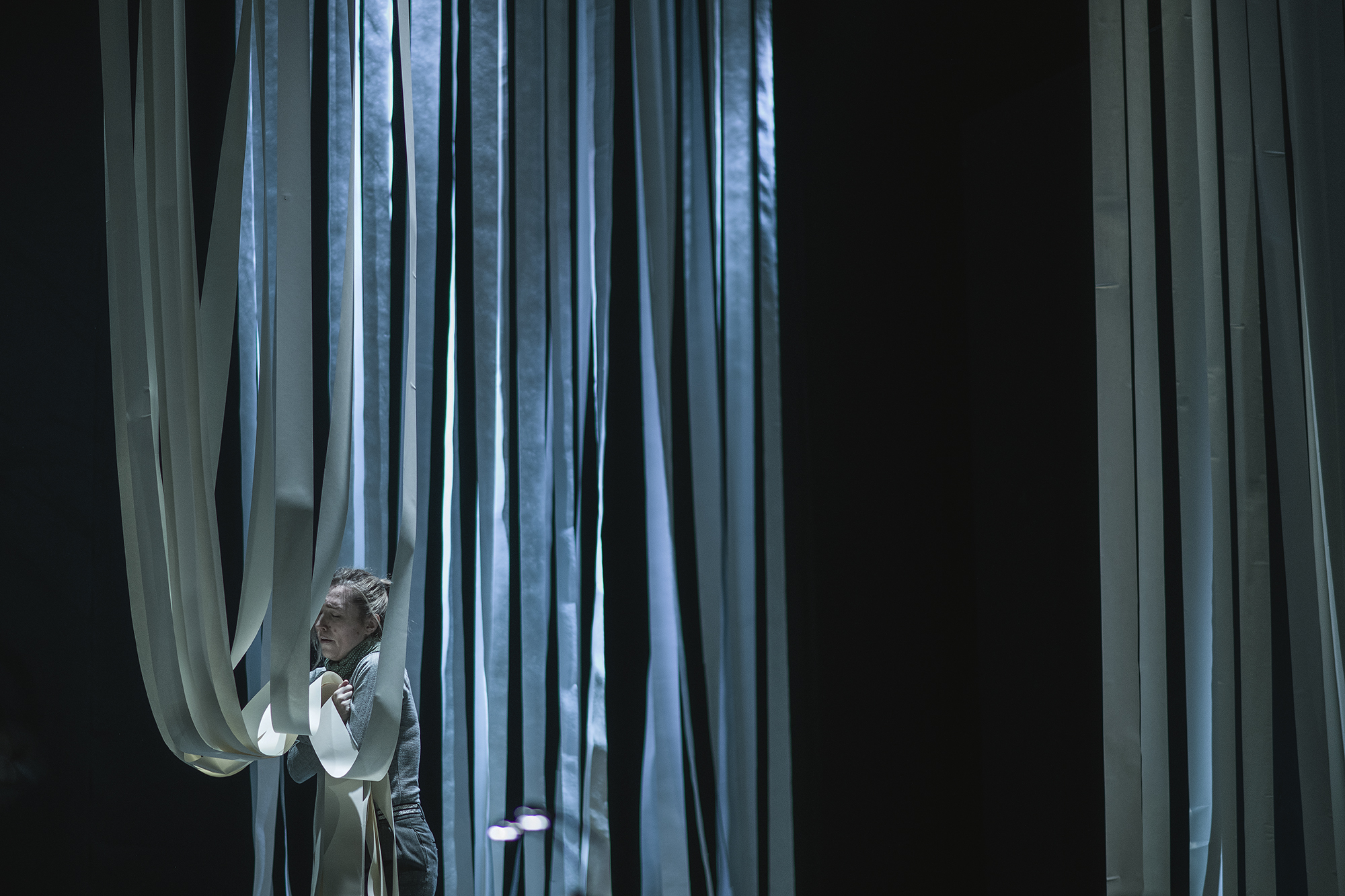

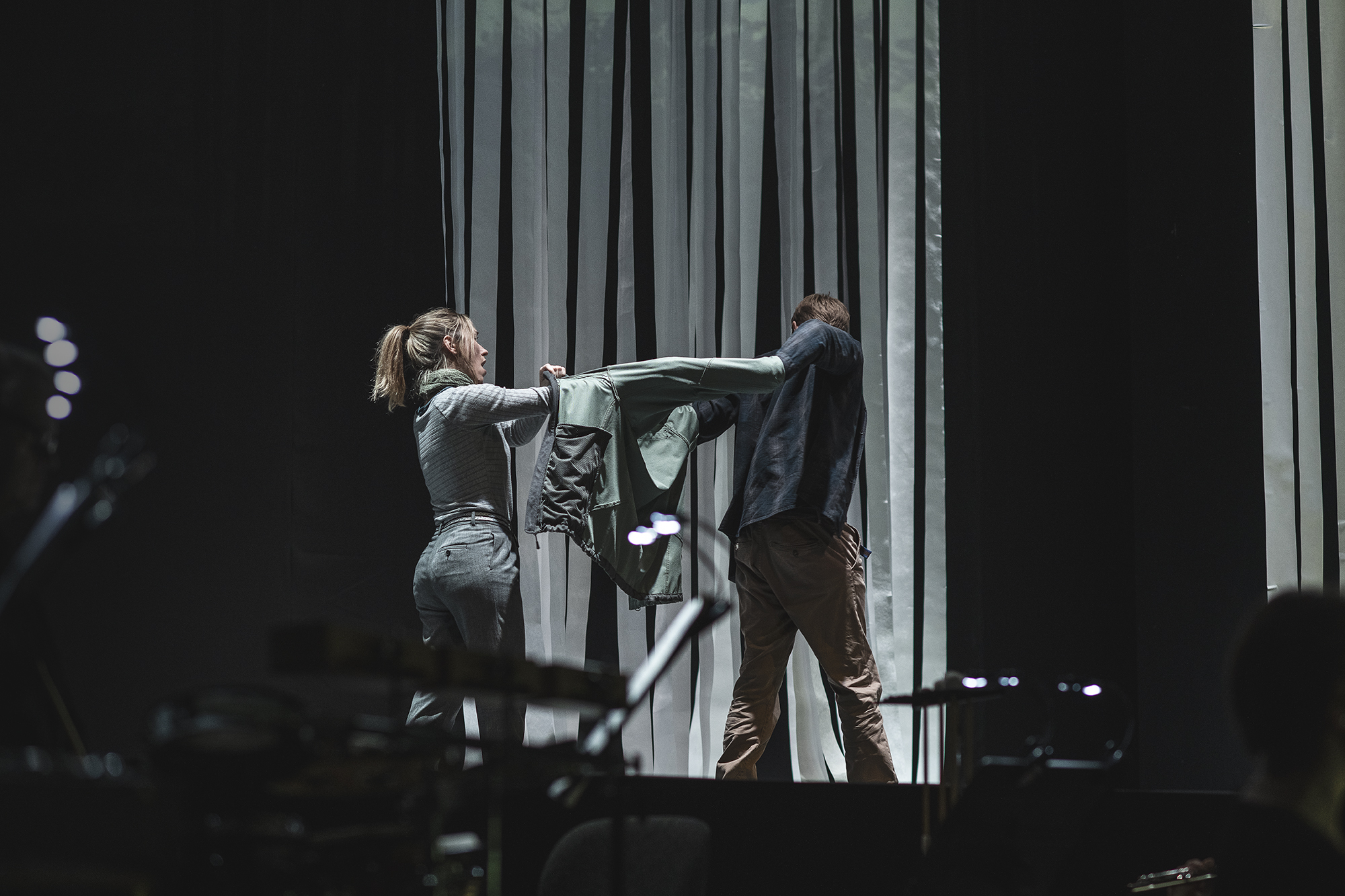

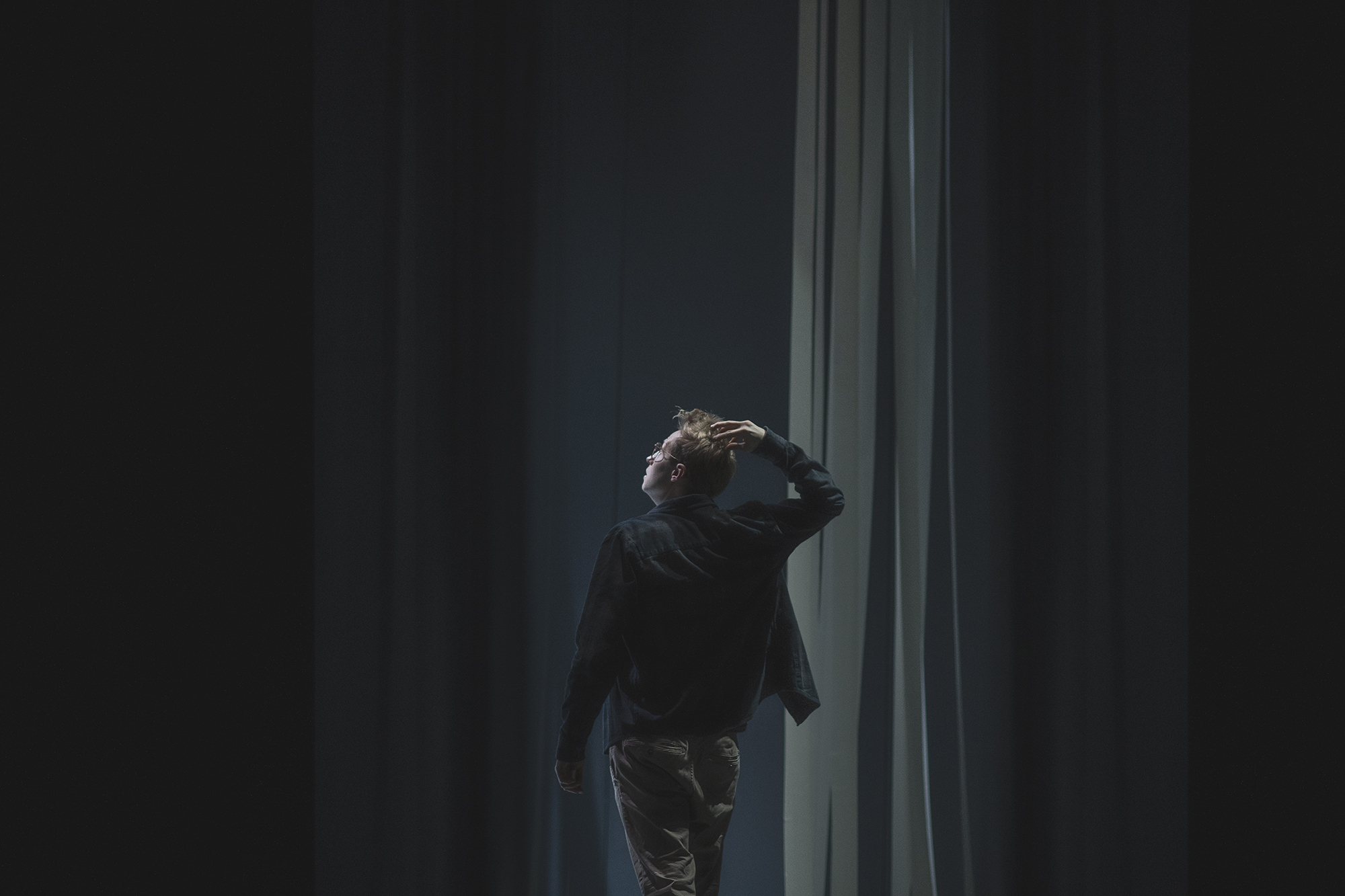

The history of the German anti-Nazi student organisation, which manifested their opposition against the authorities and called upon society to unite against the rulers has not been forgotten – and definitely not by the world of opera. Udo Zimmermann returned to the subject a couple of times. As a university student, he scored his brother’s libretto, and more than a decade later, he started working with the text by Wolfgang Willaschk. Weisse Rose is devoid of dramatic plot – instead, the piece focuses on the analysis of the protagonists’ emotional states in the final moments of their lives. Seeing their impending demise, the Scholl siblings – Sophie and Hans – gradually lose the clarity of their thoughts, delve deep into their memories and give in to unreal, idyllic fantasies (Sophie) and nightmarish visions (Hans). By standing in opposition to the authorities they did not believe in and calling upon the society to view them from a critical point of view, they raised the universal subject of awakening the nation and speaking against evil and injustice.

Focusing on the protagonists’ emotions and experiences, the analysis of a gradual descent into madness and the very way the music was created clearly allude to the Expressionists of the first half of the 20th century – its Viennese representatives chief among them. The musicians of Sinfonie Orchester Biel Solothurn built the tension by playing anxiety-inducing ostinatos – personally, I could not get the repeating harp leitmotif out of my head for quite a while – coupled with sudden dynamic and texture contrasts. The instruments employed opened up a vast space for sound experiments. The delicate, oneiric sounds (especially the harp, violins and flute) were juxtaposed with brutal and blunt ones, while both in music and the libretto, reality mixed with fantasy, underscored by colourful and flickering sound spots. I found the a cappella parts the most poignant – due to the accompanying sense of loneliness and fear. The voices of Marion Grange (soprano) and Wolfgang Resch (baritone) meshed perfectly with each other, and their singing was clearly unforced, free and honest. Their performances were devoid of wild vibratos and exuberant interpretations – instead, their singing was full of simplicity and authenticity, despite having to perform difficult parts based on far-reaching changes in melody.

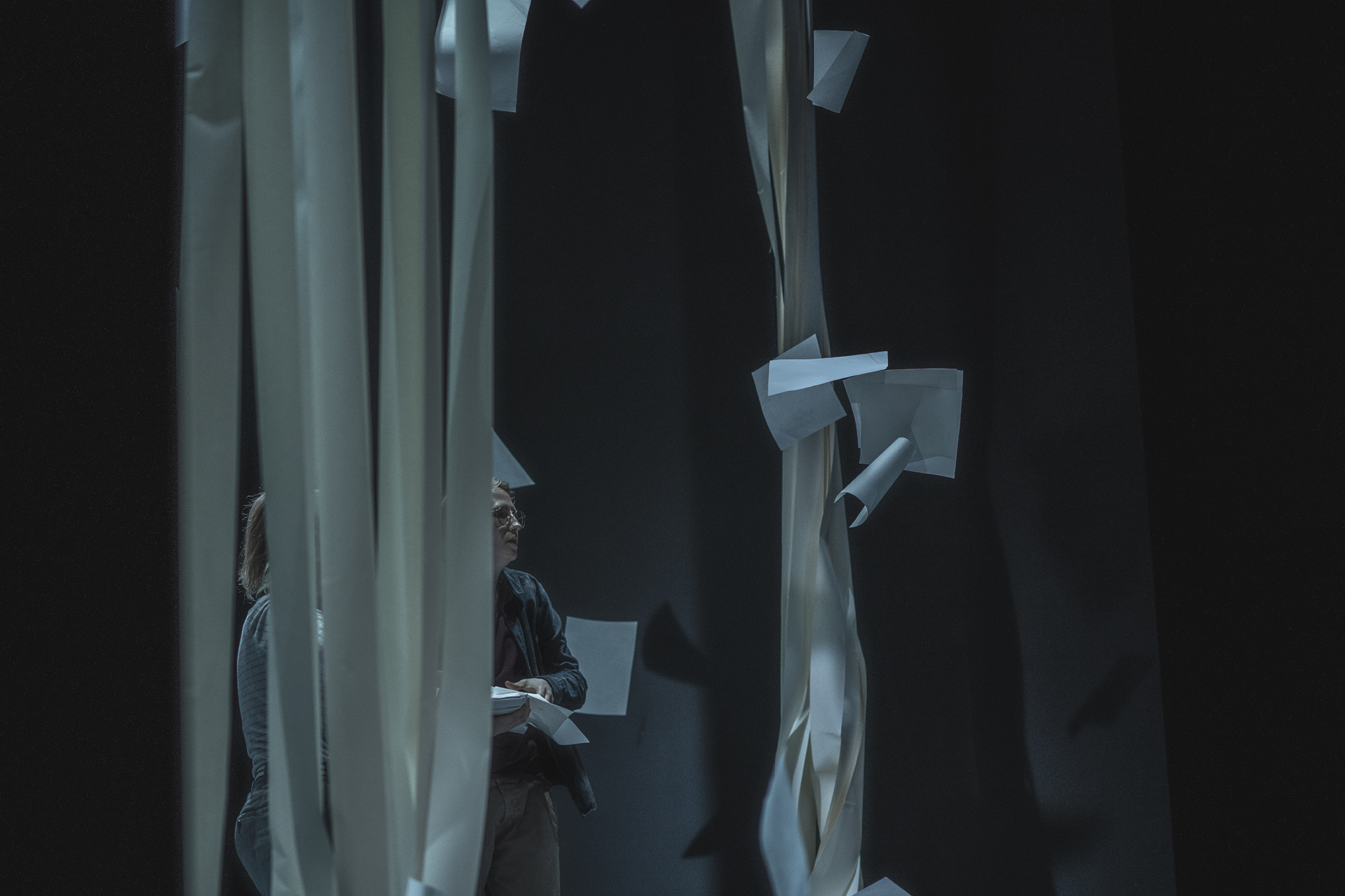

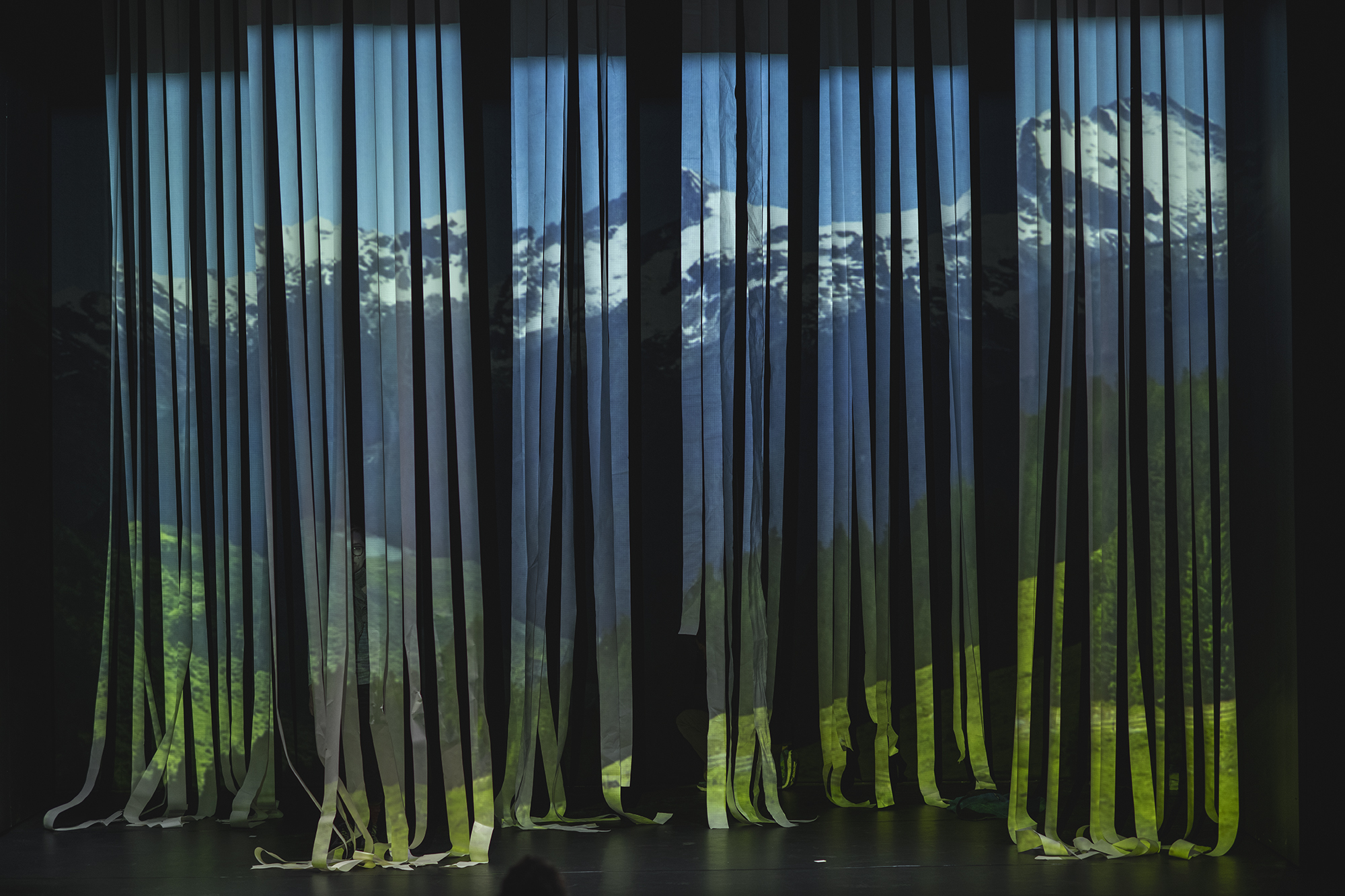

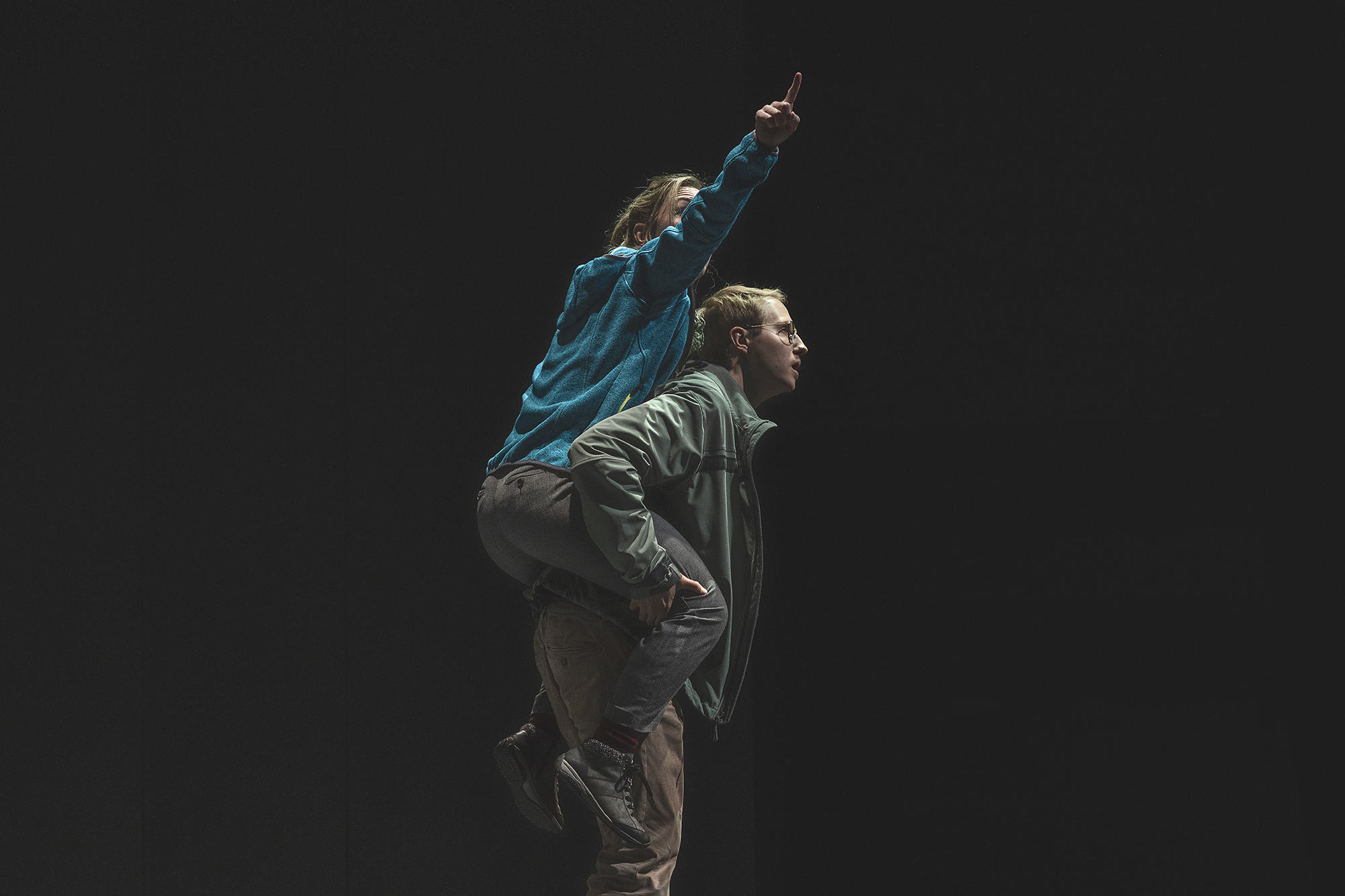

The raw and dark hall of the Małopolska Garden of Arts made for a perfect set for the award-winning staging by Anna Drescher. The changes in her minimalist stage design emerged along with the growing anxiety of the protagonists, whose world – even the imaginary one – kept gradually falling apart. Do Sophie and Hans actually live in the same reality? They both crave closeness, warmth and touch of another human being, while not seeing each other – the entire work has only a few parts where they sing together.

Willaschk’s libretto does not distort the facts – the siblings are going to die, yet they are willing to uphold their beliefs to the bitter end. The final scene is a manifesto – a call to the audience, urging them to oppose indifference towards harm, stupidity and hostility. Despite its pastoral sound, the excerpt from Franz Schubert’s Piano Quintet in A major, which clearly refers to his Die Forelle, which rang out at the end of the opera, gained a new stronger meaning in the context of Zimmermann’s piece – even in seemingly calm times, we need to be vigilant to see the danger threatening our freedom in time.

Maryla Zając for the Krakow Festival Office

- fot. Edyta Dufaj

- fot. Edyta Dufaj

- fot. Edyta Dufaj

- fot. Edyta Dufaj

- fot. Edyta Dufaj

- fot. Edyta Dufaj

- fot. Edyta Dufaj

- fot. Edyta Dufaj

- fot. Edyta Dufaj

- fot. Edyta Dufaj

- fot. Edyta Dufaj

- fot. Edyta Dufaj

- fot. Edyta Dufaj

- fot. Edyta Dufaj

- fot. Edyta Dufaj

- fot. Edyta Dufaj

- fot. Edyta Dufaj

- fot. Edyta Dufaj

Sigismondo, with a libretto by Giuseppe Foppa, is based on its authors’ fantasy about Poland, which was nowhere to be found on the world maps at the time of its premiere in 1814. Using literary fiction, they showcased the universal themes of tolerance towards otherness and the impact of emotion on decision making.

Trusting the words of his jealous minister Ladislao (Władysław), King Sigismondo (Zygmunt) accuses his wife Aldimira of adultery and sentences her to death, which leads to the threat of a war with Hungary – King Ulderico wants to avenge the death of his daughter. The plot thickens: Aldimira is alive, saved by Zenovito (Ziemowit), one of the courtiers. After many years have passed since her apparent death, the king meets a woman who bears a striking resemblance to his late wife – who is actually Aldimira – and agrees with Zenovito’s idea that she should try and pass for the queen for Ulderico’s benefit. Ladislao is unable to stop scheming in order to win over the woman, which ultimately leads to his defeat.

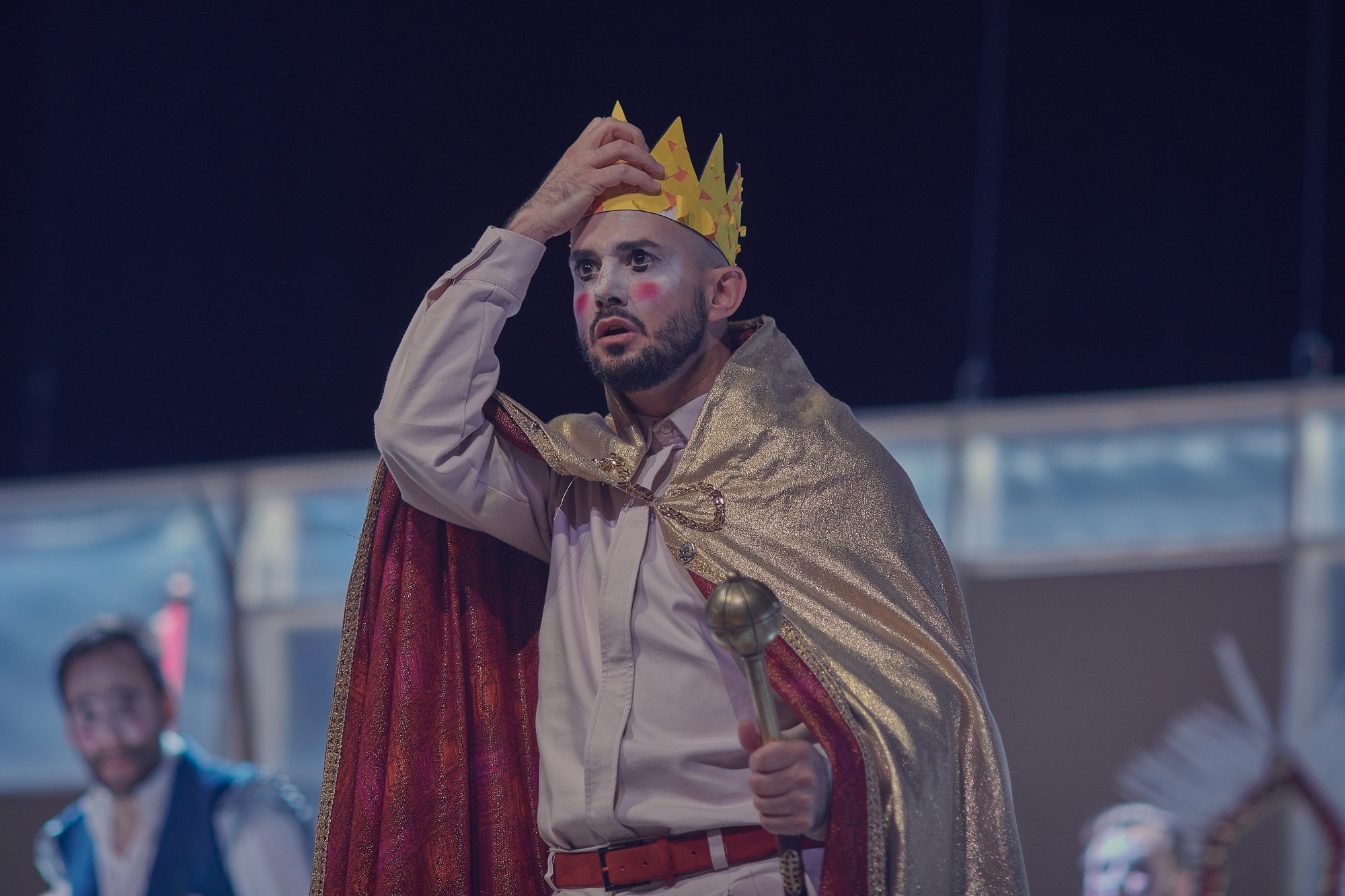

Sigismondo in a humorous and brilliant rendition by Krystian Lada refers to well-known Polish symbolism from our art and everyday lives. The opera abounded in references to Matejko’s works, plays of colourful lights, contrasts and textures affected by the matte smoke and the bright shine of stage lights. The way the protagonists were spread around the hall of the Juliusz Słowacki Theatre also contributed to the painterly nature of the work. The choir – showcasing their vocal and acting skills – presented various vivid images on stage throughout the play. The video materials employed by the director – both intimate and delicate, as well as comical ones – diversified the piece and were naturally intertwined with the plot. The way the opera staging referred to commedia dell’arte highlighted the theatrical and fictitious nature of the story, which is more universal than it seems to be at the outset.

Sigismondo is characterised by a number of musical ideas known from other works by the maestro of bel canto. The bold jumps in melodies and exhausting coloraturas based on long staccatos were naturally and unobtrusively combined with the instrumental music performed by the musicians of Capella Cracoviensis under the baton of Jan Tomasz Adamus, artistic director of the festival. With his three-octave scale, Franco Fagioli (Sigismondo) easily combined the precision of the breakneck vocal runs with authentic acting, starting with his first bars. The deep tenor of Pablo Bemsch (Ladislao), who played his part with a pleasant lightness, was also particularly attractive. The meticulous preparation of the perfectly coordinated duos – including the enchanting “Un segreto è il mio tormento” from the first act – deepened the intimacy of the scenes.

This year’s edition of the Opera Rara Festival raises questions about divisions and walls. Despite being an opera buffa, Sigismondo can be hardly considered comical, when we take a closer look at its deeper meaning. Under the layer of palace intrigues and plots, it explores the issues of sense of identity and community, prejudices against otherness, as well as borders and limits that we are willing to cross and exceed in order to achieve our own goals. We are in for another meeting with Krystian Lada – thanks to Katarzyna Głowicka’s Unknown, I Live With You, which will be presented soon.

Maryla Zając for the Krakow Festival Office

- fot. Klaudyna Schubert

- fot. Klaudyna Schubert

- fot. Klaudyna Schubert

- fot. Klaudyna Schubert

- fot. Klaudyna Schubert

- fot. Klaudyna Schubert

- fot. Klaudyna Schubert

- fot. Edyta Dufaj

- fot. Edyta Dufaj

- fot. Edyta Dufaj

- fot. Edyta Dufaj

- fot. Edyta Dufaj

- fot. Edyta Dufaj

- fot. Klaudyna Schubert

We no longer know where the boundaries of what we call fascism, Nazism, xenophobia, chauvinism or nationalism actually are. What is this patriotism that the greatest authoritarians hide behind so willingly? Its true sense is recalled by the actions of the members of Weisse Rose – the White Rose – young patriots who wanted to see Germany becoming free and peaceful, famous for its great culture and heritage.

Many people know this story from Marc Rothemund’s 2005 film Sophie Scholl, and now we will recall this story once again thanks to the Opera Rara Festival. The protagonists were called traitors by those who built a death machine at a scale unprecedented in history, unleashed the most heinous of wars, leading to the ruin not only of the countries they turned against, but also of their own Germany. People, who in the name of racial purity murdered a large part of their country’s citizens, ordered their countrymen to go and die in a pointless fight and preferred to see the greatest cities and monuments of German culture turn into rubble, rather than surrender. All these impressive merits to their homeland could be boasted by those “patriots” who zealously sentenced the students, who quoted Goethe, Schiller and Novalis in their leaflets, to death by beheading, while calling them the worst of names.

“Why do you allow those in power to deprive you, step by step, openly and secretly, of your rights? One day the day will come when there is nothing left, but a mechanised apparatus of state, headed by criminals and drunkards? Has the violence already crushed your spirit so hard that you forgot about your right, or rather your moral duty, to bring this system down?” – these were the questions asked by members of the White Rose in one of their leaflets. It was in Munich in 1942. A year later, this system that they exposed took their lives. “The mechanized state apparatus” worked, as they predicted, efficiently and ruthlessly. The words in the leaflet, addressed to the residents of Nazi Germany, resonate equally strongly at all times, regardless of the place. They call upon us to be vigilant in the face of the authorities that put themselves above the rights and freedoms of citizens.

Udo Zimmermann approached the musical adaptation of the story of the White Rose three times. In 1967, he wrote Weisse Rose, an opera to a libretto by Ingo Zimmermann; he developed another version of the piece the following year. The planned production at the Hamburg Opera in 1986 was to include further adaptations, but instead he decided to write a new work on the same subject, this time to the libretto by Wolfgang Willaschk. The result was a completely different work, devoid of plot and focused on the inner experiences of the two protagonists: the Scholl siblings just before their death. The stage version presented in Krakow premiered at the Theater Orchester Biel Solothurn, and its author – Anna Drescher – received the 2015 European Opera-directing Prize and the Best Opera Award at the Armel Opera Festival. The work will be presented by Sinfonie Orchester Biel Solothurn, led by Kaspar Zehnder.

For many women, their participation in the Afghan Women’s Writing Project was a true breakthrough. As Roya recalls: I took up my pen to write and at first I was afraid: what to write? about what? But this was a project to write about everything, and I took the pen; I didn’t write from outside of my heart, I began to write about whatever was in my heart… The writing project gave me a voice, the project gave me courage to appear as a woman, to tell about my life, to share my pains and experiences. I wonder how big the change in my destiny is because of your work and this project. Who would trust an online class, a writing project, to change a destiny and a faith? AWWP gave me the power to feel I am not only a woman; it gave me a title, an Afghan woman “writer.” … I took the pen and I wrote and everything changed. I learned if I stand, everyone will stand, other women in my country will stand.”

AWWP is a project initiated by an American journalist, Masha Hamilton. She came to Afghanistan following the leads of a story of a woman murdered by the Taliban for killing her husband. Trying to find out more about the case, she started reading articles, reports and books. She quickly realised that this did not bring her closer to truth, because women’s voices were always mediated – constrained and distorted by husbands, fathers, brothers, relatives and biased media.

Hamilton went there to talk to the Afghan women in person. This experience and the resurgence of the Taliban prompted her to set up a project that would encourage women to express themselves through writing and telling her own stories. Many of them had to take part in it secretly. The journalist wanted to support the Afghan women, convinced that telling one’s story is a human right. “Though it sounds simple, I cannot say how important I think this is in a country where women have been told their stories do not matter, and urged to be silent, and warned against honesty.”

Hamilton’s account shows that while writing essays and poems about their experiences, the Afghan women were empowered, they gained strength, courage and self-confidence. They started changing their surroundings. The project helped them gain computer literacy and critical thinking skills, along with the ability to use the language consciously, which bolstered their professional competencies. Sometimes, when applying for a job or a school, they attached works written as part of the AWWP under the supervision of professional editors. Some have become lawyers, journalists and even parliament members. Their voices proved to be important, if only because they often have a moderating influence. They do not start new conflicts, instead they are able to build bridges. That is why it is so important that these voices are heard and that they become part of the general debate.

The opera installation, which gives them a stage, composed for three singers, a string quartet, electronics and dancers, with performance directed by Spanish conductor Pedro Beriso, is a joint work of director and playwright Krystian Lada and composer Katarzyna Głowicka.

Join us for the meeting kicking off the 2020 Opera Rara Festival, which will be attended by Robert Piaskowski (Representative of the Mayor of the City of Krakow for Culture), Nicholas Payne (director of the Opera Europa international association) and Karolina Sofulak (director of Vanda, one of the operas slated to be presented during the festival).

This year, the Opera Rara banner brings together varied styles, which are connected by a common thought. The festival makes us wonder why we are so eager to build walls around ourselves, what are the consequences of this, and what to do to build bridges instead of them. Should we treat opera as a fortress, cut off from the rest of the world, where only the art of beautiful singing is cultivated?

Opera has always been able to react in a quick and robust manner by keeping a close eye on social moods and attitudes, commenting on reality, insulting kings, inspiring revolts, as well as taming dictators or making them furious. There is no reason why it shouldn’t tell us about the world here and now – either by referring directly to current events or by reflecting them in the mirror of the past.

One question remains – are we still ready to listen to what is has to say in the 21st century?

23 January, 5:00 p.m., Juliusz Słowacki Theatre, Mirror Hall

Flavour-Filled Opera Rara is a project accompanying the Opera Rara Festival, which invites the audience to the table, partially as a way to complement the experience of the concert and make it fuller, thanks to the sense of taste. The previous editions of the festival offered a number of opportunities to sit at the table. During the meetings in Krakow’s restaurants, the invited guests explored the links between culinary and fine arts, treating the performance watched that evening as a starting point for discussions and debates. Renowned guests, such as Tessa Capponi-Borawska, Agnieszka Drotkiewicz, Łukasz Modelski, Marek Bieńczyk, Robert Makłowicz and Wojciech Nowicki convinced the attendees that cuisine can perfectly complement the artistic experiences.

Also this year, the concerts of the Opera Rara Festival will be followed by dinners and debates about the works themselves, their authors, inspirations and the times in which they were created, as well as the cuisine of the bygone era. As the project coordinator Bartek Kieżun points out – “Flavour-Filled Opera Rara is a unique meeting of high culture aficionados with the best restaurateurs in Krakow – a clash of connoisseurs of the tasty and the beautiful.”

Following the performance of Sigismondo, join us on Thursday, 23 January at 9:30 p.m. for a meeting with Robert Makłowicz, which is slated to take place at the Albertina Restaurant (Dominikańska 3).

The libretto of the opera does not reveal the name of the Polish ruler that its authors had in mind. Perhaps it was Sigismund I the Old? Or maybe Sigismund II Augustus? There is a chance that it was Sigismund III Vasa; however, the reign of these three rulers covers nearly 150 years of Polish history in one of its most interesting periods. We will ask Robert Makłowicz about what exactly was going on with the cuisine back in the day. Together, we will discover whether Queen Bona actually brought soup greens to Poland, how a Polish ruler from the Swedish dynasty enriched the Polish table and how people used to toast back in the day.

On Tuesday, 4 February you can join us at the Karakter Restaurant (Brzozowa 17) for a meeting with Adrianna Stawska-Ostaszewska and Magdalena Kasprzyk-Chevriaux, following the performance of Enoch Arden.

Enoch Arden is a classic poem of the Victorian era, the plot of which reverses Homer’s Odyssey. We will take advantage of this enormous time span and talk about the most delicious bites in the history of the culinary arts. We are going to explore the process that made cooking the first thing that distinguished us from other beings, learn who ate the capon and who had to do with mussels, and why the great Velázquez focused on an old woman frying eggs.

On Monday, 10 February at 9:30 p.m., following Il ballo delle Ingrate, you can come for a meeting with Tadeusz Pióro, which is planned to take place at L Concept 13: Bar & Restaurant 13 (Main Market Square 13).

Monteverdi’s Il ballo delle Ingrate is a truly unique piece, composed for the wedding of the son of Prince Vincenzo Gonzaga, in the style of French ballets de cour. Since the Italian court at the turn of the Baroque and Renaissance is an interesting subject – not only from the standpoint of the cuisine – we will try to discover what such a weeding could have looked like, who cooked and what dishes were served. Have Italians always believed that less is more in the kitchen and that three products are enough to prepare a culinary poem?

All meetings will be hosted by Agnieszka Łopatowska – journalist specialising in literature and travel. Lifestyle Sector Director at the Interia Group.

The festival is organised by the City of Krakow, the Krakow Festival Office and Capella Cracoviensis, with the support of the Juliusz Słowacki Theatre.

The project partners are Albertina Restaurant, Karakter Restaurant and L Concept 13: Bar & Restaurant 13.

Media patronage: Kuk Buk, Project coordinator: Bartek Kieżun.

American soprano and university professor Caitlin Vincent published an article in the summer of 2019, and even its title gave rise to heated debates: “Opera Is Stuck in a Racist, Sexist Past, While Many in the Audience Have Moved On.” According to the author, classic works from the opera repertoire – pieces dating back to anywhere from 100 to 300 years ago, contain some content that can make many of today’s viewers nervous and leave them shuffling in their seats. Their librettos contain elements completely out of line with current ethical standards – in the day and age of #MeToo, the constant struggle for racial and sexual equality and the diversification of representation, the message presented by many works may be objectionable. The examples given by the scholar are perhaps contentious, and some of her recipes for remedying the situation (rewriting librettos!) gave rise to great resistance among readers, but even if you disagree with all her arguments, you simply cannot ignore the fact that there are operas that are filled to the brim with sexism.

One of the most prominent examples of this is Magic Flute, filled with “brilliant” sentences that make you roll your eyes, as well as claims that women do little and they talk a lot, men have to lead their hearts, otherwise women will lose their way, and that women have feminine brains – and the contexts of these claims leave no doubt that the word “feminine” is used here as an insult. What to do with such works in the opera? It is hard to imagine that due to such phrases, opera houses around the world would drop one of Mozart’s most popular stage works. The translation could make some things far less obtuse, but operatic works are rarely translated these days. Or maybe we should follow Vincent’s suggestion and change the wording in the translation displayed above the stage? At that point, we will be dealing with a strange duality – we’ll hear one thing and read another. A viewer who knows the language will understand everything anyway, and people who rely only on the translation will be misled. What about changing the text? Each work tells us something about the times when it was created – it would be a shame to lose the truth of a historical moment embedded in it, even if it is painful for us. The key role in this respect is played by the director, who can deal with misogynistic texts in various ways without changing as much as a letter of the original work.

The case of Il ballo delle Ingrate is not so drastic, however, the sexism of its libretto remains quite glaring. The piece pays no attention to the needs of the women themselves and they are criticised for not being eager to meet men’s erotic desires. The latter see no criticism at all, because in this piece, women should always be ready to give pleasure, even against her will and desires. In the performance presented at the Opera Rara Festival, Monteverdi’s work will be supplemented by compositions by young Polish composer Teoniki Rożynek, who will bridge the gap between the Baroque and contemporary times. Her music was described as something that “has the power to create images” and “seems to be sculpted directly out of the sound matter.” Cinema buffs may have heard their music in the soundtrack for Jagoda Szelc’s award-winning film Tower. A Bright Day. The troublesome message of the work will challenge director Magda Szpecht, who represents the same generation as the composer. The accompanying Capella Cracoviensis will be led by one of the most outstanding Polish harpsichordists – Marcin Świątkiewicz.

Tomasz Domagała: How does the story you’re adapting to the stage fit in with our times?

Krystian Lada: When I start working on an opera I don’t know, I try to understand the composition structure of the work. And I’m not talking about musical composition, but about the deep structure of a given opera as an artefact, a testimony of human history at a given time and place. What does this work tell us about the people who brought it to life and for whom it was created? Is it possible to build a bridge from this intellectual-emotional abyss to the present day? This conversation with history never ends, because it is a part of the present day, and historical processes are intrusively repeated within a given nation or community. This is fascinating because it gives us a chance to understand and learn something about our ancestors and ourselves. I am fascinated by those moments in history which, repeating themselves, grow to the rank of archetypes, because I believe that they have something prophetic about them – they can not only bring us closer to the way things were back then, or help us to understand what is happening here and now, but also to experience the future. It’s the same with staging an opera. I want the spectacle to update and generalise – archetypise itself – at the same time, to have these two dimensions because then it can also be prophetic.

TD: So, if one of Sigismondo’s heroines is Poland, will you also tell us something about us in your show?

KL: Rossini’s opera is the story of a king who is convinced that he killed his wife, condemning her to death for adultery. Though the king has more and more doubts about the latter – whether it was adultery or if he was mistaken. The queen lives in hiding, and the king doesn’t know it. As the action develops, we discover that the queen was excluded from this society by a trick that even the king doesn’t know about. We also find out that she is not a flesh and blood Pole with, but a descendant of the rulers of an “enemy nation”. The manipulated and exaggerated spectre of the ruthlessness of the Queen’s father allows politicians in Sigismondo’s state to manipulate the king’s decisions.

And since the king’s name is Sigismondo, it’s easy to associate him with one of our three Sigismunds: the Old, Augustus or Vasa. As luck would have it, each of them had a wife who wasn’t Polish. And in each of these stories, whether it be the Italian Bona Sforza, the Hungarian Barbara Zápolya, the Lithuanian Barbara Radziwiłłówna or Anne of Austria, we have the motif of Polish nobility, dissatisfied with the fact that the king’s wife is of foreign origin. Suddenly, it turns out that this is not a single anecdote, but a basso continuo – a theme that is often repeated in our history. On the one hand, we literally marry this otherness, on the other hand, this otherness sickens us; on the one hand, we are glad that we had Queen Bona, who, according to legend, brought us soup greens, on the other hand, it is known from history that she wasn’t awaited in Poland with open arms.

Thus, this solution in the form of absolute exclusion – a death sentence – was in Sigismondo a visualisation of this emotion, which was apparently present in the society of those times. Reading this libretto in Europe of 2020, I have the feeling that it really doesn’t take long to confront questions about otherness in our society. I’m thinking about European society, because I left Poland 16 years ago, so my relationship with it is also a relationship of a kind of Polonicum: observing what is happening in Poland from a distance, from the outside, from the perspective of changes taking place in Europe. This allows us to see certain regularities faster, more clearly than when we are immersed in it, on site in Poland. I think that the whole of Europe also has to answer some questions which Poles face today: the role of national histories and the autonomy of national ambitions in the context of the idea of European unity, but also the place for non-European cultures in this community. In Sigismondo, Rossini juxtaposes historical facts in an ahistorical way. And I think it will be a fascinating game for the Polish audience, which will recognise certain elements of the folklore of our native history faster than the audience of the premiere of this work at the Teatro La Fenice in 1814 in Venice.

TD: Could you elaborate on this idea of historical facts arranged in an ahistorical way?

KL: The 22-year-old Rossini composed Sigismondo to the libretto by Foppa, who was his senior. None of their previous works dealt with Polish themes. What is more, in September 1814, preparations began for the Congress of Vienna, during which the so-called “Polish question” would be one of the important issues. Poland had not been on the map of Europe since 1795. As a result of the Third Partition of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth the lands belonging to it were divided between Prussia, Austria and Russia. So, Rossini and Foppa wrote an opera about a country that did not exist – a country that at that belonged time to Europe’s “fairy tale past”. Rossini probably knew as much about Poland as he did about Algiers from his L’italiana in Algeri which premiered a year before the staging of Sigismondo. Sigismondo was his fantasy about a country that was once one of the most powerful states in Europe. What’s more, Rossini sets the action in the 16th century – the golden age of Polish history. As a result of the Union of Lublin of 1569, the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth became one of the strongest powers in Europe – geopolitically, culturally and economically. And it is in this time that Rossini set the action of his opera. In his “operatic fantasy”, he mixed several recognisable facts. The action takes place in “Gniezno, the legendary capital of Poland”, which since the 11th century no longer served this function, but to this day remains the mythical cradle of the Piasts. Therefore, Rossini juxtaposes historical facts in an ahistorical way. The fascination with Poland of the 16th century is not new in the history of the opera of that period. In 1791, Luigi Cherubini’s opera Lodoïska premiered in Paris, and five years later, Simon Mayr’s La Lodoiska debuted in Venice’s La Fenice (where Sigismondo had its premiere). Both operas were inspired by episodes from the novel by French author Jean-Baptiste Louvet de Couvrai Les amours du chevalier de Faublas, which describe the love of a Polish princess named Lodoiska and the Polish aristocrat Lovinski. In this story, Poland is a “fairy tale land” at the crossroads of cultures – a kind of barbaricum, a locus of fiery love stories – as Asia would later be for Puccini and Verdi, as the Orient was for Mozart before.

I began to wonder where I would look for such an experience of ahistorical historicity in Polish art, in Krakow. It is always important for me to discover the local context of a given work. And so, to my own surprise, I found Matejko. There will be a lot of references to his work in our performance, because while working on Sigismondo, I rediscovered him for myself in a completely new context. Matejko’s paintings are an iconographic model of Polish history for my generation. I talked about it many times with Natalia Kitamikado, the set and costume designer. If I asked you what any of these three Sigismunds looked like, there’s a 90 percent chance you would describe a face from one of Matejko’s paintings – the one that was probably hanging on the wall of your primary school classroom, or the one on the notes in your wallet. What’s interesting is that, as in the case of many images in Matejko’s historical paintings, it is probably the face of one of the painter’s Krakow acquaintances or friends. Matejko even immortalised his wife in Polish iconography, as she repeatedly lent her face to Queen Bona. Natalia and I realised that what Rossini and Foppa did was the same thing that Matejko did – on the one hand, in a tragic moment of our history, he referred to our Golden Age, and on the other hand, he created a similar ahistoricity from elements of his own fantasy and reality. I’d like to tell you an anecdote. In the painting The Prussian Homage, there is the figure of Andrzej Kościelecki, the Great Treasurer of the Crown – or as we would call him today, the Minister of Treasury – of Sigismund the Old. In the painting, he’s standing over a large plate of gold coins with the image of the king, which were scattered to the crowd gathered by the stage of this event – it was a kind of political marketing of the time, an attempt to attract the citizens of Krakow to the Market Square. And this minister has a fantastic gold cap on his head. Natalia, who has long analysed the 16th century fashion in Poland, came to me and told me, “Listen, Krystian, nothing in these paintings makes sense!” Because of course we bow to Matejko’s authority – if there is a golden cap in the painting, that means it was a historical fact. And yet, that doesn’t match 16th century costumes at all. So I spent the following months studying clothes from the 16th century and Matejko’s paintings, and it turned out that the cap on the painting was a model of the cap of the Jewish women of Krakow in Matejko’s time, which the painter liked so much that he said that someone must have one in this painting. And so, it went to the treasury minister. In fact, a lot of things in these pictures doesn’t match the historical truth. Treasurer Kościelecki himself died in 1515 – he could have only participated in the historical Prussian homage 10 years later as a ghost (wearing the cap of a 19th-century Jewish woman…). Similar stories repeat themselves in many of Matejko’s paintings – this building wasn’t standing in this place or wasn’t there at all, this person had already died or wasn’t born at the moment of a given historical event. So, this historical fantasy has its source in a kind of “artistic archaeology” – in Matejko’s case literally, because the painter was a collector of historical objects documenting life in past eras. So suddenly it turns out that what functions for whole generations as a visualisation of Polish history is basically a fantasy on this subject.

Matejko’s ambition was not to document history, but to resurrect faith in Poland and patriotic feelings during a dark period of our history. In our show, the central point of reference is Matejko and his Prussian Homage as a moment of “getting up off your knees” by persuading someone else – in this case the Grand Master of the Teutonic Order – to humble himself and fall to his knees before the Polish ruler. This is an interesting moment, because at that time, the Poles thought they were a power and nobody threatened us anymore. And this despite the fact that in the middle of Matejko’s painting, we see a glove, thrown like a challenge, and a worried Stańczyk announcing that although it seems to us that the Prussians are on their knees, we are grossly mistaken. In this painting we also have both Sigismunds – the Old One and Augustus – father and son, and the whole elite of Polish nobility (often with the faces of Matejko’s friends) and “Her Ladyship”, as Jan Matejko used to call his wife Teodora, dressed as Queen Bona.

I consider this phenomenon, this method of work of the Rossini–Foppa duo, as well as Matejko’s, consisting of an ahistorical approach to historical facts (and artefacts) or creating a legend, fiction based on historical facts, to be the quintessential phenomenon of history. History in this sense is always a narrative that is rewritten – by artists, politicians, journalists. It’s as if it wasn’t about what really happened, but about the interpretation of these events, and about who tells the story, who arranges and interprets it for us. In this way, national patterns are modelled and political decisions are justified. This is the real power – the power to interpret and re-enact history. It is a tool for social engineering and cultural revolution. This history is often whitewashed: it removes uncomfortable facts or figures, turns a blind eye to injustice in the name of the idea of great national history. And perhaps this is why it is worth remembering today that Matejko, “the most Polish of Polish painters”, is in fact the son of a Czech, and on his mother’s side, a descendant of a Polish-German family. The Golden Age of Poland, of which we can be so proud today and to which we return in times of crisis and national tragedies, is the period of its greatest multicultural blossoming, religious tolerance and coexistence of many nations forming one state organism.

TD: So, is Matejko and Rossini’s method also Krystian Lada’s method? Will the reality of Sigismondo be encrusted with our modernity?

KL: How do you translate this into the language of the theatre? How do you create a space that is a kind of collage of historical references and allusions – a staging that glorifies history by taking events into the land of fantasy and legend? My ambition is to discover and reveal the scheme behind this. I’d like the viewer to answer the question of who is who on stage. This is the case with Foppa and Rossini’s libretto – whether you read this story from the perspective of Krakow or Brussels, you can see a reflection of reality in it. We have in this opera a leader of a state who makes bad political decisions due to personal trauma. We have the tragic consequences of mixing emotions with politics. You don’t have to add anything to Rossini. It is more likely to be a matter of creating scenic images that will stimulate the imagination of the audience.

I am inspired here by poetry and painting, especially Malczewski (who was, by the way, a student in Matejko’s historical painting class). What fascinates me about him is that everything is symbolic, historical and concrete at the same time, that it is his face and self-portrait, and at the same time Hamlet, which grows to the rank of an ambiguous symbol, which can be read both in the Polish and in the wider cultural context. My ambition is to approach this kind of handling of images that are neither hermetic nor pop-cultural, but suggestive, communicating with the most intuitive emotional layers. Images that can be read like poetry – each time anew to discover successive layers of meanings and see successive references. Just like Wyspiański’s Wedding or Piwowski’s Cruise is always “about us”, here and now, but also “about us”, as a nation then and always. For me, this is the highest form of sublimity when it comes to juxtaposing poetry with history and modernity. That is what fascinates me now. So, if there is any reference to today’s reality in Poland, it’s just that.

Interview conducted for the magazine accompanying the Opera Rara Festival held in Krakow on 23.01-14.02.2020.

Krystian Lada – director and librettist. Active on international opera scene, lives in Belgium, where he worked as the director of dramaturgy at the La Monnaie National Opera. In 2017, he founded The Airport Society collective. The first winner of the Mortier Next Generation Award for exceptional talent in the field of opera.

Tomasz Domagała – theatre critic, member of the Polish section of the International Association of Theatre Critics (AICT), Polish Radio journalist, author of domagalasiekultura.pl blog, selector of the Divine Comedy Festival and FNT Festival in Rzeszów.